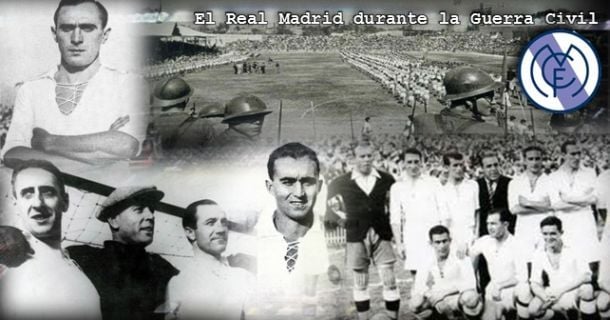

Real Madrid, like the vast majority of Spanish football clubs, suffered the impact that the Civil War left on Spain between 1936 and 1939. Being located in the capital of the country, the damage was obviously more notable. Yet just days after war, a campaign was initiated to bring life back to the club.

In 1936, Real Madrid was already a power in Spanish football. They had won 2 Ligas, 6 Copas, as well as 18 Madrid championships, 4 Mancomunado Trophies, and 2 Federation Cups. And almost a month before the coup d’état that unleashed the civil war, they faced Barcelona in the final of the Copa Presidente de la República (today known as the Copa del Rey, or King’s Cup).

For their part, Barcelona had in their trophy cabinet one Liga, 8 Copas, and 21 Championships of Catalonia; they were also considered one of the giants of Spain. In their path to the final, they had defeated Sporting Gijón by an aggregate of 4-0, Espanyol with an aggregate of 4-2, and Osasuna, whom they defeated 4-1 in the semifinals. Real Madrid made their way with a 2-2 aggregate against Arenas de Getxo, winning the tiebreaker match 6-1, and then defeating Athletic Club 3-1 and humiliating Hércules in the semifinals with an aggregate of 8-2.

Madrid FC (named as such then due to the formation of the Republic in 1931; the crown on the shield and the title “Real” in the name were eliminated) and FC Barcelona disputed, in a one-off match, the final in the Mestalla Stadium in Valencia on June 21, 1936.

The match had an extra special touch; Ricardo Zamora had announced it would be his last match as a professional footballer. Zamora, known as El Divino, had decided to retire from the football pitch at the conclusion of that mach.

The match

The shape of the teams is visibly quite different from what is common in modern football. Real Madrid fielded the best team available: Zamora; Ciriaco, Quincoces, P. Regueiro, Bonet, Sauto, Eugenio, L. Regueiro, Sañudo, Lecue and Emilín; Barcelona were without their star defender, Zabalo, who was replaced by Bayo: Iborra; Areso, Bayo, Argemí, Franco, Balmanya, Vantolrá, Raich, Escolá, Fernández and Munlloch. It was the first Clásico ever played as a Cup final.

The goals came early; Eugenio opened the scoring for Madrid in the 5th minute, while Simón Lecue made it 2-0 in the 12th minute. When everything seemed favorable for Los Blancos, the young culé, Escolá, pulled one back on the 25’ mark.

The game continued at this result until the most important play of the match. The goalscorer Escolá shot from outside the area at Zamora, who despite not seeing the ball because his teammates blocked it from his view, utilized his vast experience, instincts, and reflexes to make a full length diving save on the swerving shot; this according to accounts from the time period.

People even thought that the ball had gone in, as the dirt raised by Zamora when he grabbed the ball had clouded their vision for a few seconds.

A few minutes later, Ostalé, the match referee, whistled for the end of the encounter. El Divino Zamora was carried around the pitch by his teammates, waving goodbye to the legendary 35-year-old goalkeeper. With a 2-1 victory over Barcelona, Real Madrid had won their seventh Copa.

The Civil War and the fates of the players

On July 13th, with the assassination of José Calvo Sotelo, the general Emilio Mola began the conspiracy to revolt and on the 17th the coup d’état occurred. Having failed in the biggest cities of Spain but succeeded in others, the war was drawn out for three long years in which all sports were affected, above all football, which had become immensely popular and was already the most prominent in Spain.

The majority of the Real Madrid players departed for their home cities. Sañudo, for example, returned to the Torrelavega of his birth, advised by his father, who owned a few shoe businesses. Ciriaco, one of the best defenders of the era, retreated to his native Eibar.

The foreigners Alberty, Bizassy and Kellemen (Hungarians) and Giudicelli (Brazilian) returned to their native countries as soon as the conflict began. There was also the case of Antonio López Herranz. He departed for Mexico, to play for Club América during the years of the civil war; he returned to Real Madrid after the war ended and later played for Hércules, where he retired. Afterwards, he returned to Mexico, where he stayed the rest of his life. As a coach, he won the league with Club León in 1951/52 and managed the Mexican national team in the World Cups of 1954 and 1958.

The Madridista legend, Don Santiago Bernabéu, also served in the military. In this time he served as a member of the junta directiva, but his name was already known in Spain. He was even photographed in public on more than one occasion with the uniform of a soldier. However, Don Santiago was never involved in any armed skirmish.

A few players were involved in situations in which the death of their friends and family or even themselves came close to occurring. According to Fernando Berlín is his book “Heroes de los dos bandos” (Heroes from both sides), Hilario Marrero, a bench player from that Madrid of 36/37, saved the life of Paco Trigo, a goalkeeper who had recently signed for Racing Santander. Some Falangists detained the keeper and ordered him to come with them; all of this inside a cabaret in La Coruña. It was then when Hilario suddenly arrived, whom the Falangists recognized. They asked for Hilario’s autograph, who then presented Trigo as “the famous goalkeeper of Santander”. Hilario asked them where they were taking Trigo. The Falangists sheepishly abandoned their plans and ended by asking the goalkeeper for his signature as well.

The most active players during the war without a doubt were Emilín, Pedro and Luis Regueiro, José Ramón Sauto, and El Divino Zamora. The first three participated actively, through football, as propaganda of the Basque government. The other two witnessed the war from up close.

Emilín and the Regueiro brothers

As expected, the war stopped the progress of football in general. In the same way, it halted the development of various footballers that were already very famous and among the best in the world. The most notable case is that of Jacinto Quincoces (who together with Ciriaco and Zamora made up the best defensive threesome in the world). He amazed the fans at the World Cup in Italy 1934 and was named by experts as the best defender in the world in that tournament. Due to the conflicts, he returned to his native Barakaldo and although he returned to Real Madrid in 1940 to play another two years, he was never the same.

Other cases are those of the brothers Pedro and Luis Regueiro and of Emilín. The Regueiro brothers arrived at Madrid FC from Real Unión, one in 1931 and the other in ‘32. Emilín arrived in 1933 from Arenas de Getxo.

The three had been Spanish internationals and their careers were growing; in addition, they had won undisputed starting places in each season they played with Real Madrid - something quite difficult in that time period.

Pedro and Luis were republicans who, at the beginning of the war, despite not going to the front of the battle, participated in acts of propaganda in favor of the Republic and the Basque government. Some time after, it was said in the Spanish capital that Luis Regueiro had died in a hospital in Madrid from a bullet caught at the front lines of the war. This was categorically false; it was just a strategy from the nationalists to damage the morale of the enemy camp.

The Regueiro brothers, together with Emilín, spent their time during the war playing in benefit matches for orphans, brigades, and hospitals, to mention some of the causes that they wished to aid.

The three, being Basques from birth, were named by the government of Euskadi in 1937 to take part in a tour of matches throughout Europe and the Soviet Union. All with the aim of winning resources for the Basque fighters, who fought tooth and nail against the National army in the northern part of the country.

They traveled to France in April of that year and the team was composed of some of the best Basque players of the time. Some, like Quincoces and Ciriacos, were nationalists, and did not make the journey. Simón Lecue declined the invitation, as did Eugenio, all of whom were Madrid FC players. After the first match they received the news of the bombing of Guernica, which caused the team morale to plunge. Luis took the role of team leader and together with the coach, Manuel López, succeeded in raising the spirits of his teammates to continue the adventure.

After half a month playing in Paris, they traveled to Poland, where they played just one match and after that, went on the the USSR. It is told that Luis Regueiro had to address the Soviet authorities on many occasions about their republican values and the fight against fascism.

Everything changed once more with the news they received while in the Soviet Union: Bilbao had fallen. At that point, the players could not return home, so they continued playing matches throughout Europe. They arrived in Denmark and then returned to Paris. There in France, the players considered their situation. One player from Athletic, Gorostiza, returned to Spain to change sides and fight in the war. The club Racing de Paris offered the brothers Regueiro the option of training with them to maintain form, and the brothers accepted.

However, in December of 1937, the Regueiro brothers and the rest of the Basque team departed for America. They arrived in Mexico, where they played more than 15 matches, all with a great reception from the Mexicans. They also passed through Cuba and arrived with barely any money in Argentina. In the spring of 1938, FIFA forced the Basques to cancel all of their remaining matches. They also made the team stay two months in Argentina. They survived in Buenos Aires thanks to the help of the Spanish community that lived there. After that, they returned to Cuba.

In the summer of that same year, they succeeded in convincing the Mexican Football Federation to allow them to participate in the official league, under the name Club Deportivo Euskadi. They were league champions in 1938/39, and after that the team dissolved. Some players remained in Mexico while others returned to Spain.

As for the Regueiro brothers, they remained and founded the Club de Fútbol Asturias in Mexico, together with other Asturians that had arrived on Mexican soil due to the war. They brought their whole family to Mexico and remained there. For his part, Emilín went to play in Argentina with San Lorenzo. Despite meeting various Basques in Argentina, when the group returned to Spain, Emilio “Emilín” Alonso declined the invitation and went to live in Mexico, where he remained for the rest of his life.

Ricardo Zamora and the escape that ended in France

Recently retired as a professional after winning the Copa, Ricardo Zamora remained in Madrid to spend his holiday, and after the outbreak of war and the Siege of the Cuartel de la Montaña, El Divino was one of the names mentioned most often to be imprisoned. All of this for working for a Catholic newspaper in the city; few know that Zamora balanced his career as a journalist with his footballing career.

He sought refuge with some of his friends and after the campaign against him lasted a few days, he was finally detained and sent to the Modelo prison.

The ex-goalkeeper was in the Modelo prison during the Paracuellos massacres, which he was able to avoid. There is an anecdote told by his son that claims that Zamora was at one point about to be shot: “He told us that one time he was going to be taken out of the prison with a group of prisoners, surely to be shot, when he was recognized by a soldier who saved his life. The soldier told him to follow and he was able to escape from the prison and the bus that would have brought him to a sure death,” according to declarations taken from the website Guerra en Madrid.

They say the savior of Zamora was Luis Gálvez. He saw the Divino in the line of inmates and raised his voice to say that he was his friend and many times he had given him food to eat. He added that Zamora being there was an injustice and then hugged and kissed him; this according to the writer Ramón Gómez de la Serna in a chronicle in an Argentine newspaper.

The support of Zamora on part of the football associations was unconditional. They all knew who he was and what he meant for Spain. In a friendly match between Valencia and Catalonia, the captains of both sides, Iturraspe and Vantolrá, respectively rose to salute the President of the Generalitat, Lluis Companys, to literally plead with him to intervene for Ricardo Zamora, adding that they were certain that “he is not a fascist and is one of the athletes who has lifted Spanish football the highest with his efforts”.

In November of 1936, the goalkeeper was costlessd and took refuge together with his wife and son in the Argentine embassy. Food was in short supply and there were only 4 ‘bedrooms’, and it was not until the last controlled escapes in 1937 that he was able to leave Madrid. His destination was Alicante, and later, France. The rumors abounded that Zamora had died, as very few people knew his whereabouts.

Later, Franco-ruled Spain located him in Nice and was even further enraged when it was discovered that he had played friendly matches wearing the uniform of Nice.

Zamora gave a few interviews while he was in France; the most significant one was published in the Correspondencia de Valencia, where the keeper said: “Tell people in Spain that I am not a fascist and my only desire is to return there, to work for my country with total security”.

One of the most interesting events occurred on December 8, 1938 when the war was on its last breaths and the Catalan had returned to Spain. That day, the greatest defensive threesome in the world came back together in a friendly match between Real Sociedad and players from the nationalist camp; Quincoces, Ciriaco, and Zamora played together again.

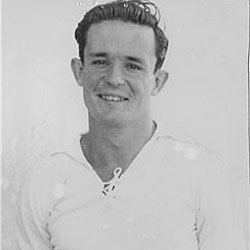

Sauto, the Mexican that served in the military

The Mexican José Ramón Sauto, who was the first of his nationality to play for Real Madrid, found himself balancing his football career and his military service in the Cuartel del la Montaña in that summer of ‘36. Due to being a recognized footballer, he had privileges that not everyone possessed, although he had to fulfill his duties in the barracks with regularity.

Luckily for the Mexican, the day the barracks was attacked, he was not there. The Fuerzas de Asalto and the Guardia Civil seized power in the barracks, leaving many of the player’s comrades imprisoned or dead.

Sauto was wandering throughout Madrid, taking refuge in a few different houses, but one day the garrison of La Montala found him and imprisoned him. They sent him to the secret police committee at the Plaza of Santa Barbara and he was there for several hours, although he was finally set costless.

He did not hesitate to take refuge in the Mexican embassy in Madrid. After more than two months there, an escape to Valencia was organized, and from there, a boat to France. At the end of February in 1937, some 400 people including Sauto and other Mexicans departed for France. However, once in France, Sauto made the decision to return.

He quickly arrived in Pamplona, nationalist territory, and he enlisted in the Battalion of Camilo Alonso Vega as a motorcycle messenger. Sauto was responsible for transmitting orders from the superiors to all of the front lines of the action - quite a dangerous job. He also participated in the famous Battle of Brunete.

Sauto was described as an undisciplined player in that he did not like to train, and after the war he continued at Real Madrid for a few years. He had good relations with Santiago Bernabéu, who asked him to return to the team. Sauto agreed but with the condition that he did not have to participate in training sessions.

In a footballing sense, the final against Barcelona was one of his best and at the same time most bitter memories, given that he left the match injured. He retired playing for Madrid in 1943 and was seen off with a tribute match against Sevilla.

Monchín Triana, the one who could not overcome fate

One of the favorites of Don Santiago Bernabéu, who once said: “If you want to enjoy yourself, go see Monchín”. He was considered one of the great dribblers and a great promise of Spanish football, and was later compared with Kopa. He arrived at Real Madrid in 1928 and played for 2 years as well as representing the Spanish national team.

He was a Catholic and a Monarchist, and his family was rich and lived in the center of Madrid. In wartime, Ramón “Monchín” Triana, together with his brothers and his father, was searched for by the republicans, without success until they threatened to kill his sister and his mother.

The family reunited and agreed to hide his father and that his three brothers, who were known footballers, would give themselves up. They thought that because they were footballers, they would receive a pardon. Monchín, Enrique, and Ignacio turned themselves in but there was no mercy; they were condemned to death and brought to the Modelo prison. Before being executed, they organized some football matches where Monchín Triana and Ricardo Zamora participated. On November 7th at dawn, a truck of prisoners departed for their final destination, and were shot in the Paracuellos massacres.

Postwar

On April 19, 1939, after the end of the civil war, Pedro Parages, one of the pioneer players of Real Madrid, who was also a manager and president, convened an assembly to recover the club. The war had damaged the Estadio Chamartín and dispersed the vast majority of the players and many of the socios throughout Spain. The fate of Real Madrid was in danger.

Parages, with the help of a few others, succeeded in uniting almost everyone and in the end of November 1939, with the Estadio Chamartín repaired and a squad with some new faces, as well as those who had been there before the war such as Quincoces, Leoncito, Lecue, Sauto, López Herranz, and Méndez-Vigo, Real Madrid returned anew. On December 3, 1939, the team played its first official match since before the war. The rest is history...

This report was written by Miguel Balderas for VAVEL España and translated into English for VAVEL UK. Read the original in Spanish here.

Works consulted: Real Madrid y Guerra en Madrid.

Photo 1. Team lineups. | Miguel Balderas | VAVEL.

Photo 2. Zamora’s save minutes from the end of the final | ABC.

Photo 3. Zamora carried on the shoulders of his teammates | Realmadrid.com.

Photo 4. Don Santiago Bernabéu as a soldier in the streets of Madrid during his service. | Realmadrid.com.

Photo 5. Emilín in a magazine from the age. | Guerra en Madrid.

Photo 6. Luis Regueiro shooting on goal. | Realmadrid.com.

Photo 7. Zamora before the Cup final against Barcelona. | Realmadrid.com.

Photo 8. José Ramón Sauto posing for the photo. | Realmadrid.com

Photo 9. Monchín Triana as a player for Atlético Madrid. | Realmadridfans.com.

Photo 10. The Estadio Chamartín after the war. | Realmadrid.com.