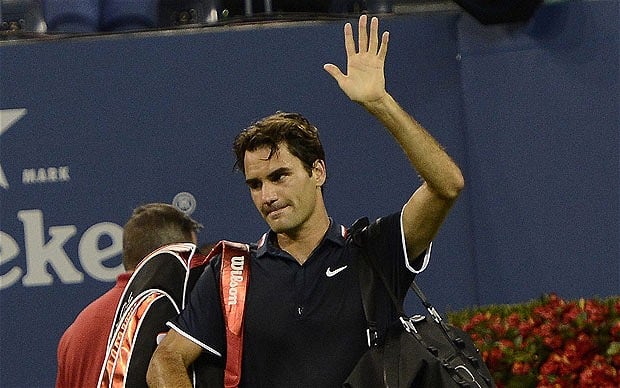

This time last year, Roger Federer was really struggling. Summer losses to Daniel Brands and Feliciano Delbonis coupled with a second-round Wimbledon exit saw predictions of the end of his career being imminent, and much talk of his long-speculated-over decline beginning in earnest. He talked of a back injury and was trying out a new racquet, but most onlookers had a different reason for his poor results – his age.

Wasn’t 32 too old to play tennis at the highest level? Should he retire now, before things got really bad? Federer was adamant that he wasn’t ready to stop playing, that he really felt he could still challenge for the biggest titles, but he found that most disagreed. A fourth-round US Open loss to Tommy Robredo only served to strengthen doubters’ convictions. He improved during the Autumn, managing to qualify for the World Tour Finals as the world number seven, and reaching the semifinals, but most still didn’t expect huge amounts from him in 2014.

How wrong we all were. This summer has been yet another reminder that one should never write off Roger Federer. He’s reached the final in his last four tournaments, winning two, and has been the tour’s most successful player over the summer. A 250 title in Halle, runner up at Wimbledon and Toronto, before a first Masters title in two years in Cincinnati – Federer has well and truly proved his doubters wrong. Such is his form that he’s forced his name into the debate over possible US Open champions, where last year it seemed his major-winning days were over.

So what’s behind this incredible turnaround? It’s not like he needs to carry on playing – with 80 titles including a record 17 majors, a record (consecutive and total) number of weeks at No.1, almost 1000 career wins and £50 million in prize money his legacy is certain.

First and foremost is his love of playing and of competition. He’s spoken about it many times, and it’s something not all players have – particularly when times are a little tougher (Andre Agassi springs to mind here). Don’t underestimate the importance of this in helping to get through his tough times – if winning’s not your only motivation, losses are slightly easier to move on from.

Don’t get me wrong, though. I’m not trying to say that Federer doesn’t have motivation to win, or that he isn’t fiercely competitive – I’d say quite the opposite. For all the descriptions of Rafael Nadal being a ‘ferocious competitor’, or all the instances of Novak Djokovic and Andy Murray letting out their frustrations on court, it’s sometimes easy to forget Federer’s own drive to win. The Swiss perhaps (generally) keeps more of a lid on it during matches than his rivals, but this is a guy who broke down in tears after losing the 2009 Australian Open final, having already won the title three times. Make no mistake; Federer’s competitive drive is no less fierce than that of his rivals.

It’s important, too, not to underestimate the influence of Stefan Edberg. He certainly hasn’t received the attention that Boris Becker has as Djokovic’s coach, where every early loss (at least up until Wimbledon) prompted speculation that the arrangement wasn’t working and could be ended. Ivan Lendl, too, attracted more attention than Edberg does, although he was the first of the former star players to be recruited as a coach, and so interest was understandably higher as to whether the arrangement would work. There’s no question of the huge impact that the Swede has had on Federer this year – he’s been markedly more aggressive, coming in to the net much more frequently, and coming to terms with the fact that serve-and-volley is a high-risk tactic in today’s game. Previously, as a match went on he would sometimes appear to lose confidence in the tactic and attack the net less and less, but the Wimbledon final was not like that at all – he continued his super-aggressive strategy right to the end, and it very nearly paid off for him. I’m willing to bet that if he’d tried to play the match from the baseline, it wouldn’t have been nearly so close. In addition, at 33 years old, there’s another reason it’s a good idea to keep points short – at 33, you’re not going to recover from endless long baseline rallies quite as easily, giving you a real disadvantage as the match goes on.

Perhaps his poor year last year has helped him this time round. He’s spoken of feeling more relaxed at Wimbledon this year as a result of having nothing to defend, and this can only be a good thing. However mentally strong you are, constant pressure to match your previous achievements is going to catch up with you sometimes. Arriving at SW19 knowing he had a chance to win the tournament, but without the pressure of matching a deep run from last year sounds like a refreshing situation for the seven-time champion, and one which could well have helped him.

Finally, of course, there’re the reasons he himself gave. A back injury, as Nadal and Murray have also discovered, can really inhibit a player without perhaps seeming to, at least not all of the time. Consider the surprise that Murray’s surgery last year was met with – since the clay season, it was assumed that things were back to normal. Trying out a new racquet was always going to bring teething problems, especially when you’ve been playing for so long with your current one.

Federer spoke at the US Open of a lack of confidence – hardly surprising after the summer he’d had, and this can be a tricky problem in a sport which has such a huge mental element. It can make players more tentative with their game, and be a real problem if one falls behind in a match. The only reliable way to regain confidence is to win matches, which thankfully the Swiss started to do more regularly in the Autumn, even if he had to wait until March for his next title. Perhaps we shouldn’t have been so quick to dismiss Federer’s analysis of his own problems.

Should Federer win the US Open, and Djokovic lose before the last four, the Swiss would take the lead in the Race to London, placing him well to finish the year ranked No.1. In a career crammed full of them, that would be one of his very greatest achievements.