Manchester United under Ole Gunnar Solskjaer exist in four phases. New dawn. Reality check. Crisis. Survival. It’s a cycle that does enough to keep the Norwegian in a job, but some distance from sustained success.

Whether or not one subscribes to the idea that he is a problem at Old Trafford, overwhelming evidence points toward a single truth: he is not the problem.

United are stagnating, but Solskjaer – whose long-term thinking so impressed CEO Ed Woodward at their first meeting – cannot be held responsible. He must look at his squad in comparison to the vision he set out back then and wonder how it came to this.

Despite an impressive third place finish and three semi-final appearances last season, this summer he was left high and dry.

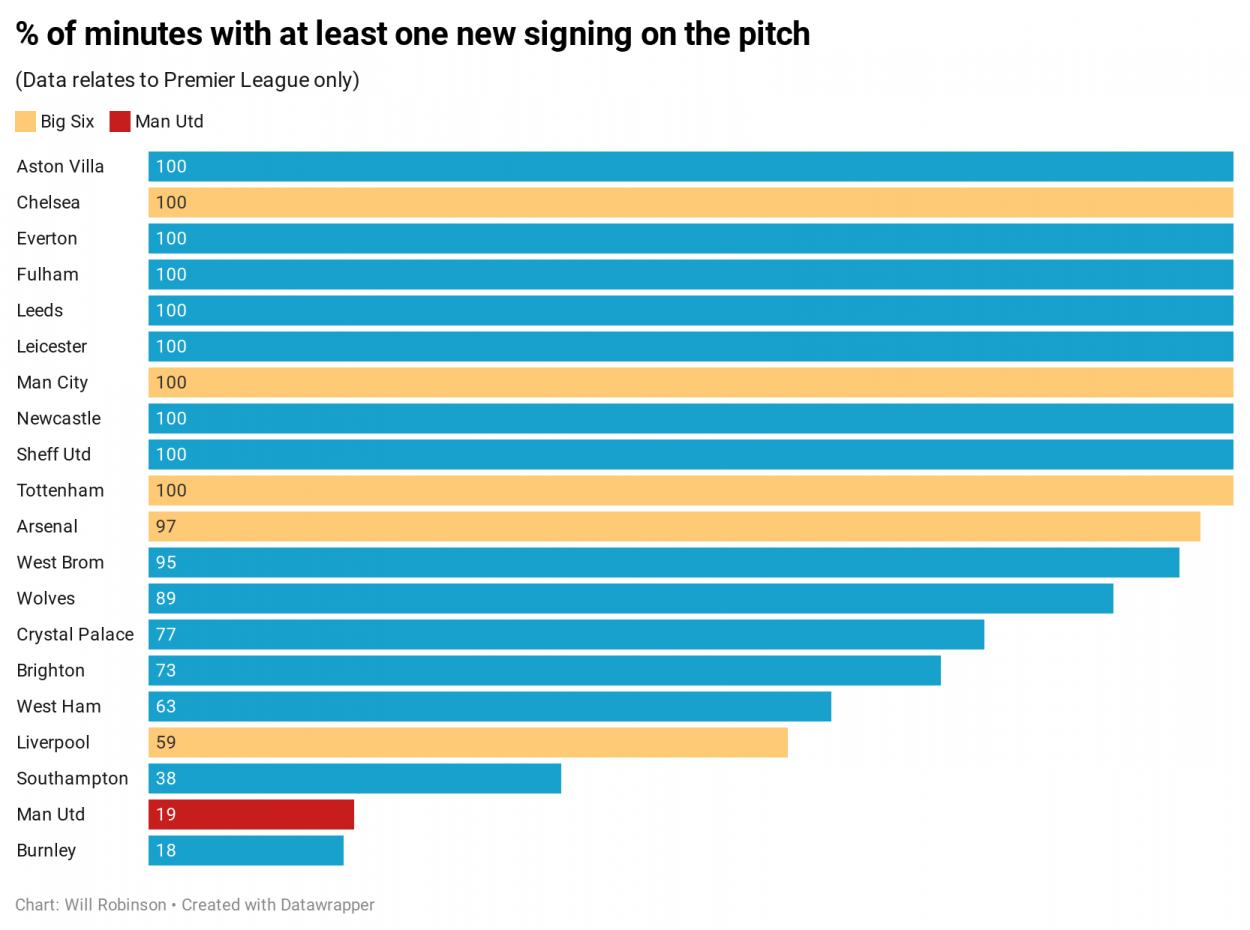

While the league around him improves, Solskjaer has been left with the same side that limped home in July. Ten teams, including top four competitors Tottenham and Chelsea, have not played a single minute this season without a summer signing on the pitch; Arsenal are close behind.

For Solskjaer’s side, it has been just 19%. For the vast majority of the time, his XI is unchanged from last season. It’s clear that, despite a frantic deadline day, United have improved their first team not one jot.

The transfer window did bring new faces, however. Indeed, when United sealed the deal for Donny van de Beek early in September, it seemed as though they might avoid the pitfalls of previous years. But despite the obvious talent, these were clearly not players high on Solskjaer’s list of priorities.

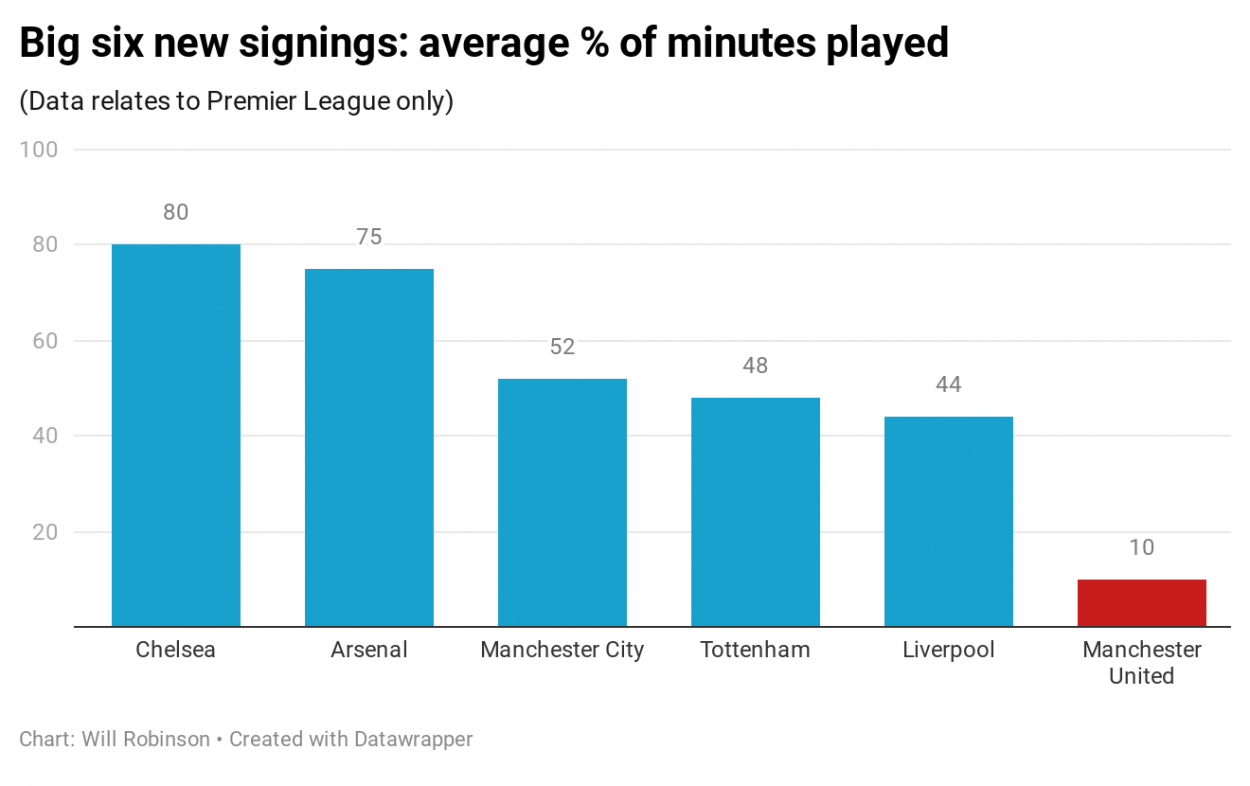

Taking into account injuries, suspensions and quarantines, United’s new signings have spent just 10% of possible minutes on the pitch – split between cameo appearances from van de Beek and Edinson Cavani.

At no other big six side have the new arrivals spent so long on the sidelines. The next lowest figure is Liverpool, who could argue it was their squad, rather than their first XI, that needed strengthening. But it’s clear that for Chelsea and Arsenal – whose managers are like Solskjaer in their relative inexperience, emotional connection to the club and their need to prove a point – summer additions have been worthy of almost ever-present status in the first team.

When criticized about recruitment, Woodward’s defence is often to point to the figures. It is true that the club has a higher net spend in recent summers than most European rivals – how much an inability to sell players contributes to that figure is a discussion for another day.

But it’s money spent poorly. Only Manchester United could go into a summer transfer window prioritizing a right-winger, sign two players in that position, and still see it as a problem area come October.

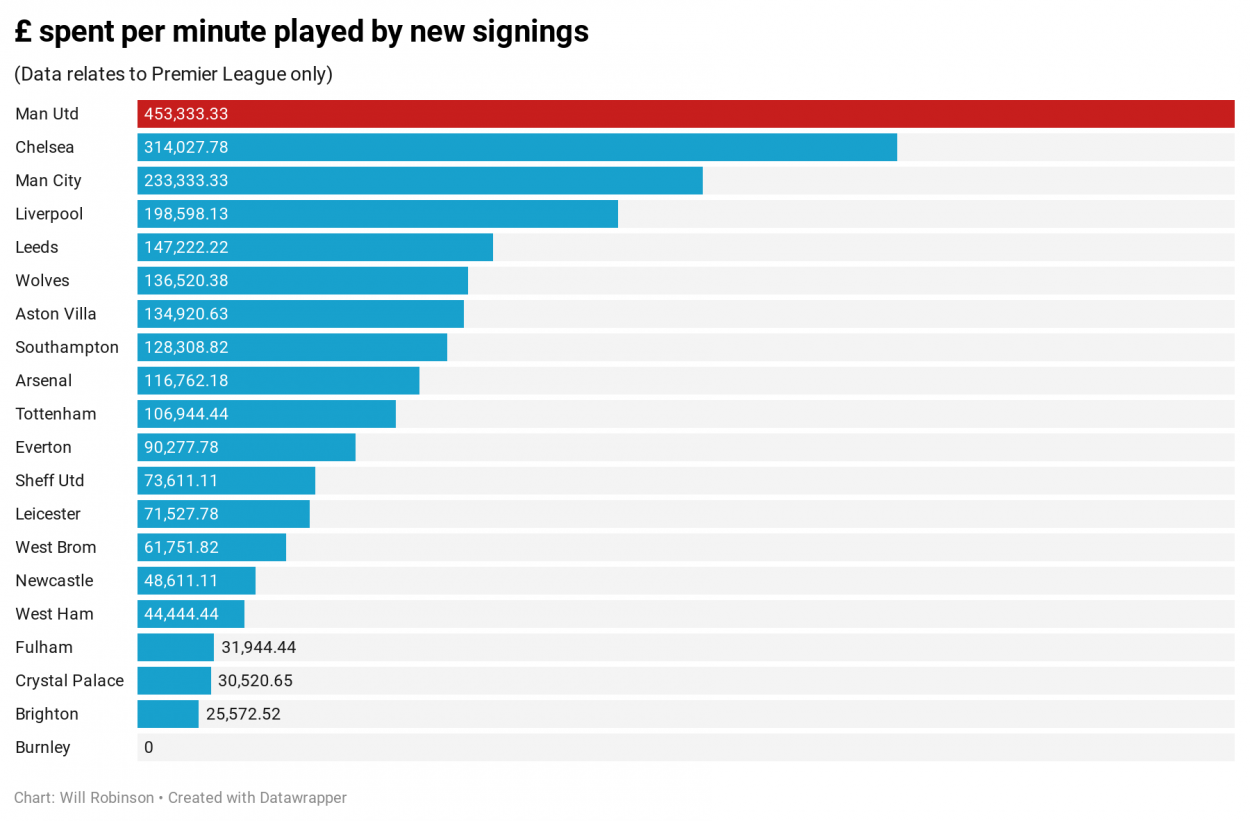

Despite their relative thriftiness this summer, the value for money from these new signings is poor.

In their inability to improve the first team, United’s business works out at more than £450,000 per minute of football played by their new arrivals. It’s more than double every other side in the league except Chelsea, who may look at the brand new spine of their team and think it money well spent.

What is clear is that when Solskjaer looks at his squad he sees far too many square pegs and no shortage of round holes. The youthful, vivacious football he wanted to pursue is being played in Germany, and witnessing Erling Haaland, Jude Bellingham and Jadon Sancho combine for Borussia Dortmund must cause him palpitations.

Despite a persuasive pitch to all three, on each occasion United failed to get the deal over the line. What remains for Solskjaer is a squad composed of contradictions: expensively assembled and yet in dire need of investment; transformed under his leadership but desperate for renewal.

With Champions League football secured, United owed it to Solskjaer to push forwards once again. They failed.

Soon, it may be someone else’s problem. But when Solskjaer looks back on that first meeting with Woodward, he may wonder how it came to this. Clearly, someone didn’t uphold their side of the bargain.

@WillRobinsonUK