Football, politics, and conflict have always had an complicated relationship. From Germany against England in 1938 to the United States against Iran 60 years later, the world’s most popular sport has often shown its versatility as a force for activism, political statement, and real change.

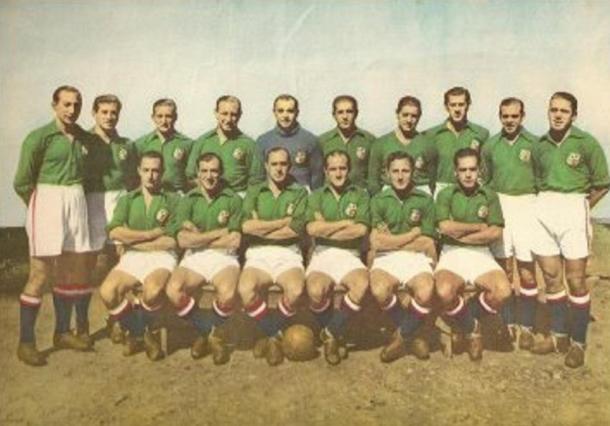

The Spanish Civil War of 1936-39 was a conflict in which football played a more prominent role than most. The Euzkadiko Selekzioa, the forerunner of the modern Basque football team, travelled the continent and then the world to win funding and support for the ailing Second Spanish Republic in their fight against General Franco’s Nationalist forces.

Euzkadi were eventually unsuccessful in their attempts, and most of their squad opted to settle in South America where they had toured and joined a local league.

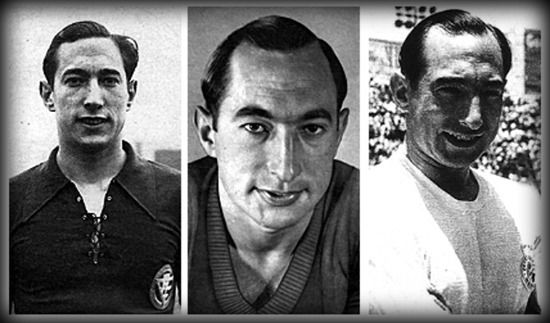

Their star, centre-forward Isidro Lángara, was one of those who remained. He signed for Argentine side San Lorenzo and did not return to his homeland until 1946. By then, though, he had already established himself as one of the most astounding footballers of the pre-war period.

Real Oviedo and the Delantera Eléctrica

Long before Real Oviedo became every share-buying football hipster’s online dream, they were one of the most exciting young teams in Europe. After winning promotion as champions of the Segunda División in 1932-33, Oviedo went on to finish third in the top flight in two of the following three seasons, and were well placed to build on this promise before football was halted by the onset of war.

Oviedo’s weapon was the Delantera Eléctrica, a whirlwind of an attack comprised of Lángara, Ricardo Gallart, Casuco, Gonzalo Galé, and Juan Inciarte.

In the five seasons Lángara spent at Oviedo from 1930 to 1936, the Delantera Eléctrica plundered 275 goals in 96 games. Even allowing for the more high-scoring nature of the game at the time – Oviedo started all five of these forwards – their goalscoring exploits were legendary.

But Lángara was the star. 81 goals in three seasons was enough to win him a trio of consecutive Pichichis and international recognition. He played 12 times for Spain, scoring 17 times and etching himself into the nation’s footballing history by scoring both goals in La Roja’s first ever win over Germany. His brace, in front of a Cologne crowd of 70,000 on an occasion dripping with Nazi German nationalism, was enough to secure a famous win for Spain and leave the Nazi officials present red-faced, their claims of German physical superiority rubbished.

The Basque team tours Europe

In 1936, though, Oviedo and Spain were stopped in their tracks by the attempted Nationalist coup of José Sanjurjo. Civil war broke out, and Lángara headed north to join the fight.

His footballing career was given a lifeline as a Basque team – the aforementioned Euzkadi – were formed with the intention of raising funds for those affected by the civil war. An initial European tour brought varied club and national opposition: Racing de Paris, Marseille, Lokomotiv, Dynamo and Spartak Moscow, Czechoslovakia, Tbilisi Dynamo, Georgia, Norway, Denmark and others.

In footballing terms, Euzkadi’s tour was a success but the fall of Bilbao to Nationalist forces left most of the squad without a safe place to return. Franco sought to unify Spain in a way which left no part for the distinct identities of the Catalans, Galicians, or Basques.

Voluntary exile in South America

Hence, the team crossed the Atlantic to South America and became Club Deportivo Euzkadi to avoid FIFA sanctions – the game’s governing body had recognised the fascist regime’s new football federation in 1938, and bowed to its demand to ‘excommunicate’ the Basque side.

An initial tour of Cuba and Mexico brought enough success for the new club to decide to settle in their new continent, joining the Primera Fuerza league in Mexico.

They joined in 1938 and played just one season, at one stage appearing on course for the league title. When the Nationalists declared victory in Spain in April 1939, though, their form seemed to be derailed. They lost their last ever game the following month 7-2 to third-placed Club España to miss out on the title by a single point and the club folded. Each player was rewarded for their efforts with a one-off payment of 10,000 pesetas, and most joined other clubs in the Mexican league.

Lángara heads south to Buenos Aires

Lángara, though, was one of only two who chose to move abroad once again. He followed his friend and teammate Ángel Zubieta to Buenos Aires to join San Lorenzo, where he quickly etched his name into the club’s folklore.

Only a few hours after disembarking the ship which carried him from the Aztec Coast, Lángara was anxious to prove himself as an ambassador for the Basque region and requested that he play for San Lorenzo in their game that afternoon. After almost a fortnight of travel, Lángara took to the field against River Plate, Argentina’s biggest club.

He scored four in 40 minutes. River, at the time almost unbeatable, were stunned and the nation had a new footballing idol. As Lángara topped the league’s goalscoring charts with 33 in 34 games in his debut season in Argentina, news of his exploits filtered home to Spain. There, among Nationalists and Republicans alike, Lángara cemented his status as a national hero.

Extending his reputation as a scorer of ‘impossible’ goals in Argentina, Lángara stayed with San Lorenzo until 1943, scoring 110 league goals – he remains the seventh-highest scorer in the history of the club.

He then moved from the Argentine capital to that of Mexico with Club España, where he remained for another three years and scored another 105 goals. There, he became the first player to earn a league top scorer award on three continents; Europe, South America and North America.

Lángara was, put simply, unstoppable.

A late return to Oviedo

In 1946, though, he received word from Spain. Football in the country was recovering and Real Oviedo wanted him back. He answered their call.

By then 34 years of age, Lángara was no longer at the peak of his powers and he would not recover his crown as the dominant force in Spanish football. He was usurped by Telmo Zarra, a frighteningly prolific Athletic Bilbao forward who would later have the trophy for the highest-scoring Spaniard in La Liga named after him.

Lángara returned to his boyhood club for two seasons in the twilight of his career, and scored another 23 goals as Oviedo finished eighth and ninth. It was becoming clear that Lángara, a symbol of Basque and Spanish sporting pride, was coming to the end of his time at the top. In 1948, ten years after leaving Spain for the first time, he returned to South America.

Little is now known about Lángara’s life after the conclusion of his playing career, though he did continue to tour South America in a managerial capacity. He lifted the Chilean league title in 1951 with Club de Deportes Unión Española and coached Puebla FC to the Mexican Cup two years later.

These achievements are but a footnote in the footballing career of Isidro Lángara Galarraga. A name barely known outside of Spain, Lángara was undeniably one of the most astonishing footballers of the pre-war period and a true legend of the game.

His career coincided with one of the bloodiest and most tumultuous periods in the history of his homeland, yet he established himself as a stunning athlete, a national icon and a symbol of anti-fascist resistance. In Isidro Lángara, football and politics found perhaps their perfect match.